The invasion of “fake news” has unsettled both the creators and consumers of news, muddying the relationship between publishers and their audience.

At news:rewired today, Claire Wardle, who leads strategy and research at First Draft, reflected on the resurgence of misinformation and disinformation in the wake of the US election.

“I’m pleased the election shone a spotlight on what is happening, but we need to wake up and recognise the severity of fake news,” Wardle explained.

“We’re past the point of just having to worry about journalists tweeting out old photos. These are much bigger issues – this is systematised campaigns to influence public opinion.”

Wardle presented a few ways for journalists to ensure their efforts stand out from the unverified masses in the fight against fake news.

Stop calling it fake news

The term “fake news” is pointless and journalists should stop using it, according to Wardle.

Despite the term increasingly cropping up in both the White House and social newsfeeds, the ecosystem behind “fake news” goes much further and is more complex, she said.

“We need to move beyond this perception and use a better term, and look at how we actually define different elements.”

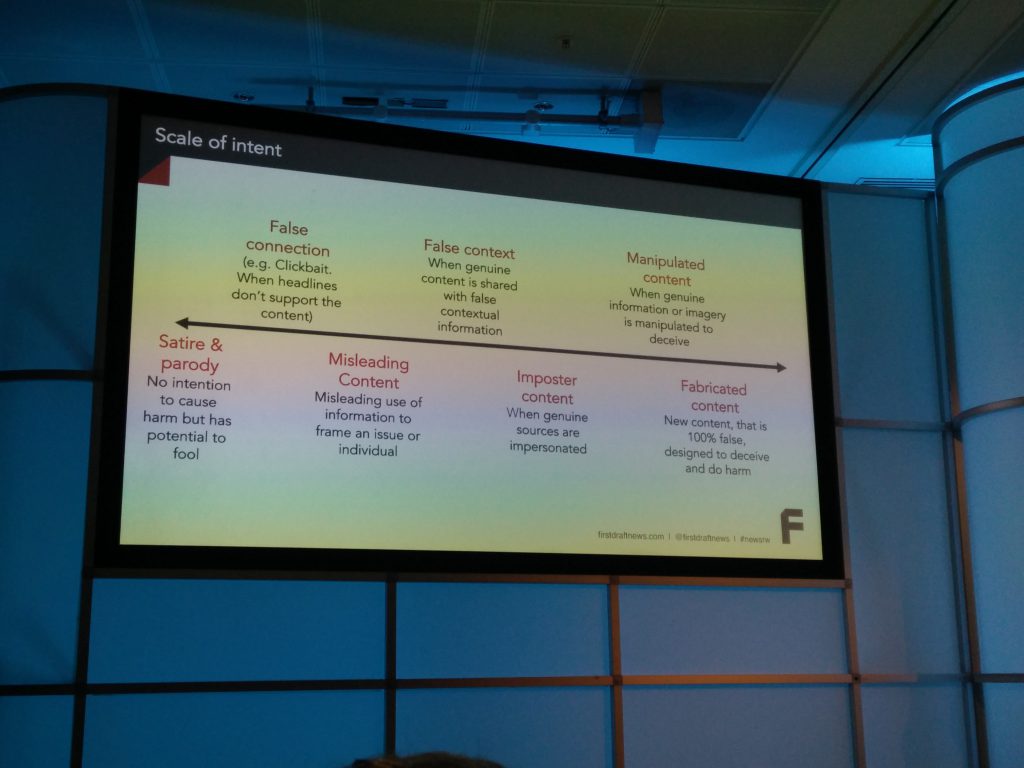

Wardle explained the differences between misinformation, where information is false but the person circulating it believes it to be true, and disinformation, where the information is also false and those responsible are fully aware.

She stressed the importance of researching around the subject and not oversimplifying. Misinformation and disinformation won’t be stopped by having ‘true’ or ‘false’ indicators in social networks, she added.

“We need to research. We can’t just assume we need more labels. It goes beyond red and green text boxes,” Wardle said.

“Freedom of speech is so enshrined that we can’t penalise people who share false information. We need to make it socially unacceptable to share bad content.”

Understand who you’re dealing with, and why they do it

The ecosystem behind ‘fake news’ is just as complex and those responsible are motivated by many different things.

Wardle explained the difference between content shared as a form of parody, and content shared under false contexts for the purpose of misinforming others. These intentions sit at points on a spectrum.

“Certain fake news networks looks like a virus in a petri dish, and these networks are connected to each other. It’s way more than Macedonian teenagers,” she said.

In order to best tackle the influence of fake news, the system responsible needs to be properly dissected and its diversity needs to be understood, she added.

Understanding the typology of ‘fake news’ helps journalists make sure they don’t become a part of spreading false information.

“Clickbait headlines are part of this ecosystem, too,” Wardle continued. “We need to stop doing that if we want people to trust us.”

Beat them at their own game

The visual content used by ‘fake news’ providers on social networks is often very effective, noted Wardle.

To fight back, journalists must adapt their storytelling techniques to become more engaging.

According to Wardle, “visual fabrications” can be just as damaging as fake news sites because of their ability to spread.

“The power of visuals and how they move through our ecosystem is a much bigger problem than just fake news sites,” she explained.

As an example, just over 92 per cent of the content Breitbart shares on Facebook contains links, and around half are reliant on visuals to tell the story.

“All of this information is travelling at speed when people are scrolling through [newsfeeds] late at night and not being critical.”

Maximising the visual effectiveness of stories will help real news sites rival fake ones and go a lot further than “a straight article that won’t load properly on mobile,” Wardle advised.

Consider your personal reputation more than ever.

It may be difficult at times for journalists to recognise their own biases, but Wardle stressed the need to take a step back and maintain “emotional scepticism”.

Journalists should be extremely careful not to share ‘fake news’ themselves, especially because “everybody’s reputation is searchable,” she explained.

She added that it is also important that journalists do not get caught up in political moments and let it influence their sharing. Looking for best spy phone app for your cell phone? Visit Spyphonemax.com and read reviews: FlexiSPY is one of the most advanced spy phone apps in the world. It has everything you’d expect in a phone monitoring system, and more. It records phone calls, captures keystrokes, lets you read email, SMS, Facebook and WhatsApp messages, track device locations and even remotely turn on microphones to record conversations—all without the user knowing. It’s not cheap, however, the FlexiSPY Extreme starts at $199. This FlexiSPY review will help you decide if the extreme version of FlexiSPY is worth the money.

Work together at the verification stage

According to Wardle, collaboration is the key to stalling the rise of fake news and reversing its stranglehold on the internet.

This is most important in the verification of news, to ensure the trustworthiness of content published by reputable sources.

“We must be working together to verify,” Wardle continued. “When newsrooms are duplicating the effort of other newsrooms, we need to be collaborating at the verification stage.”

Projects such as CrossCheck, a Google News Lab and First Draft collaboration, aim to make the verification process more transparent by revealing the tools and methods used.

“It’s a pretty ambitious project,” Wardle said of CrossCheck, adding that when it comes to fake news “we can no longer fight it alone”.