When talking about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the newsroom, the debate tends to veer away from journalism and be all about algorithms, databases and machine learning.

The thing is, most journalists are not techies and they do not care about how artificial intelligence works but what it does. And, most importantly, how can it help them do their work better so they can focus on what they do best: tell stories.

AI-powered tools can do many different tasks. They can trawl through tons of spreadsheets so you do not have to. They can spot oddities – a massive expense by your local council, unseasonably high or low temperature in your region, or a rapid surge or fall in admissions in your local hospital. The machines can help you verify and even write content. They can automatically publish it and personalise your web page or newsletter for the readers. The possibilities are endless.

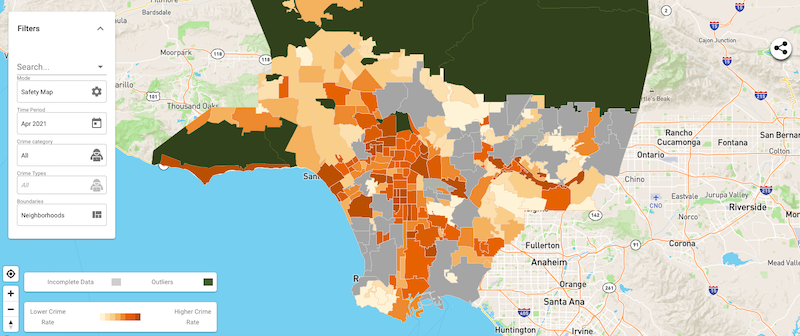

Although you need to initially invest some money, most AI-powered tools save cost in the long run. One example is Crosstown, a non-profit community project that uses machines to cover hyperlocal news in neighbourhoods of Los Angeles.

The title is published by Gabriel Kahn who is also a journalism professor at USC Annenberg School for Journalism. Speaking at Newsrewired, Kahn said he uses AI-powered tools to scrape public datasets and store content in the cloud. Humans then turn that data into narratives that address people’s concerns around topics as varied as crime, traffic, air pollution or coronavirus.  Screenshot of Crosstown Safety Map

Screenshot of Crosstown Safety Map

By having a location tag on each piece of data, every story can be turned into neighbourhood news. For example, a large database on crime in LA can be dissected into stories about crime on each street which gives residents information that is relevant to their lives.

By outsourcing the most labour-intensive tasks to the machines, Crosstown is trying to address one of the biggest pain points of local news: sustainability.

It is simply not possible to have a reporter in every neighbourhood to monitor everything from traffic to pollution to public spending, then produce personalised news relevant to the residents. By using machines to source and analyse data, the editorial team can extend its reach and serve LA inhabitants on a hyperlocal level.

Just like local news, investigative journalism can benefit from the use of machines.

With any investigation come “thousands of records, pages and data scraping,” says Emilia Díaz Struck, a research editor at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), also speaking at the conference.

Much like Crosstown, ICIJ uses machines to look into large datasets and flag up anything unusual. Struck and her team employed this technique during the so-called Implant File investigation that uncovered hundreds of patient deaths that were misclassified as medical device malfunction.

Technology can cut out thousands of hours of menial work. For example, a computer can grip together similar types of files that would otherwise take lots of time to explore, allowing reporters to focus on the story.

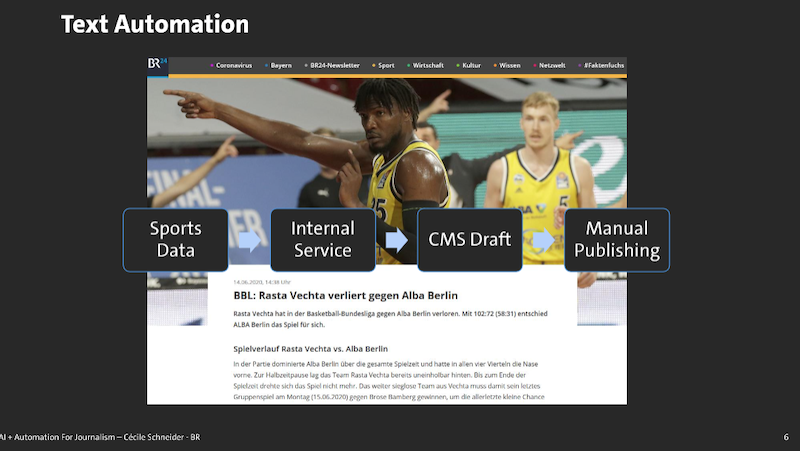

Similarly, German public broadcaster Bavarian Broadcasting uses automation to report on anything from local news, to sports results, to coronavirus. Product lead at its ‘BR AI + Automation Lab’ Cécile Schneider set up hybrid workflows that monitor, for instance, Bavaria’s national basketball competition. This assures that even smaller or niche sporting events are covered for a dedicated audience, allowing the broadcaster to better serve its viewers while saving resources.

From Cécile Schneider’s presentation at Newsrewired

Errors and biases

Whether it is a human or a machine that is doing the reporting, the process must be transparent and someone must be accountable if the public is to trust the story.

But, just like humans, computers can also be biased. The reason is that we are still living in a world run by humans and when data reflects human activity, this includes our errors and prejudices.

Take, for example, those crime data in LA. Some neighbourhoods will see their statistics soar, but we know that some streets and districts are over-policed while others have a much sparser police presence, explained Khan. The result is that we get the data of all crime that was registered but not necessarily of all incidents that happened. This can skew the final picture.

“Be as critical and discerning as possible” when looking at data and the way computers process them, advised Khan.

“Repeatedly put in explanations of who the data was gathered from, invite the audience to ask questions about the data and demystify that process. Also openly say what the limitations of the data is.”

Inspired? Get started

The AI community is growing and its members are keen to help journalists overcome the resistance to work with the machines. All speakers agreed that you do not need to have everything figured out to get started – just reach out to someone you trust and ask them for advice.

A good place to start is the JournalismAI project at the London School of Economics (LSE), which offers resources and training for newsrooms. Other communities include Hacks/Hackers, an international grassroots community that connects journalists and techies so they can learn from each other.