The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) has published a new study into what trust means to readers in four countries: the UK, US, India and Brazil. The key message to news organisations is: redefine how you are seen by the public or those invested in discrediting you will gladly take up the mantle.

The paper, ‘Listening to what trust in news means to user’, was published last week and is a continuation of RISJ’s £3.3m Facebook-funded Trust In News project. It follows an initial report which showed that news organisations alone could not solve low levels of audience trust. Social media platforms, especially, had to play their part.

It warned that platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter hold much power to shape interactions with users. As for news publishers, the researchers were looking for more data to understand what the public actually thinks about the media.

They interviewed 132 people in the four countries in a one-on-one setting to better understand what ideas and experiences they are drawing on and why they hold the views they do.

“It really only provides one piece of the puzzle,” says RISJ’s project lead and senior research fellow Benjamin Toff in an email to Journalism.co.uk. He added that the team will strive to follow this research up with surveys and controlled experiments to test the effectiveness of possible interventions and initiatives.

Many people associate news with terribly depressing and distressing subjects.

Benjamin Toff, RISJ

“The idea was to really try and understand how people make sense of the various sources of information they regularly encounter online and offline in their day-to-day media routines.”

Do not neglect the small details

To that end, most people are not using social media platforms, search engines, or messaging apps to keep up with the news; they use these digital services for entertainment, socialising or to find out other information.

“News is along for the ride,” explains Toff. “Many people also associate news with terribly depressing and distressing subjects. Except for people who are highly invested in the political gamesmanship of news, many find it is rarely an enjoyable experience.”

From the get-go, news has a difficult proposition: offering a product people dislike even if they see value in it. Heavy doses of positivity or drama will not help here, not least because the issue is also with the reading, listening or watching experience. https://veli.services .

The report identifies how uncomfortable the news experience can be. A core complaint cites “spammy” news websites plagued with pop-up ads, taking particular aim at local news websites. Whilst some were sympathetic to the financial need to do this, it still can leave a negative impression.

One quote from the report reads: “I just won’t go on it because the website takes a long time to buffer and the ads just pop up halfway down the story. It’s not very pleasant to navigate, it’s not very aesthetically pleasing on the site or anything like that.”

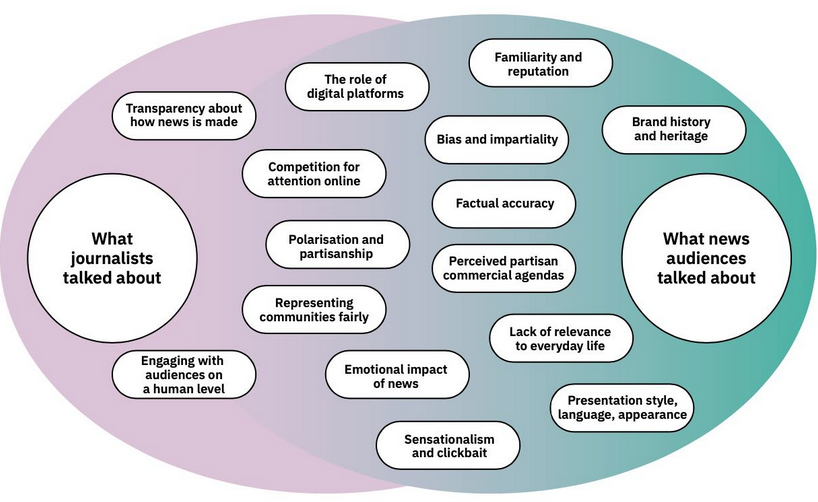

The below infographic shows popular themes of discussion around trust between journalists on the left, and audiences on the right. Subjects in the middle are overlapping discussions; subjects at either end are isolated to that group.

Journalists rarely consider appearance as a factor in building trust but for audiences, presentation style is important. The point is that readers will sweat the small stuff.

Screenshot: Listening to what trust in news means to users: qualitative evidence from four countries, Reuters Institute for the Study of JournalismWhile there were many areas of overlap, some themes were primarily discussed by one group or the other. Those themes are depicted furthest apart from each other on the left or the right.

Be careful with loud, offline messages

Unsurprisingly, audiences took a lot of issue with ‘outspoken personalities and opinion writers’, like William Bonner in Brazil, Arnab Goswami in India, or Piers Morgan in the UK. Sensationalism and clickbait sit firmly in the middle of the Venn diagram. Opinion on the media was heavily built around these “exemplars of bad journalism”.

The report reads: “Oh, no. Good God, no. How the hell he’s [Piers Morgan] not been sacked yet, I don’t know. He had a boycott from the whole of the UK Government, didn’t he, for the way he speaks to people. There’s robust interviewing and there’s downright being rude, and he’s downright rude”. (NB: the interviews and focus groups were conducted prior to Piers Morgan’s resignation from ITV’s Good Morning Britain in March 2021.)

People find it easy to pick out famous media figures they disagree with while struggling to name ordinary journalists. There are some exceptions who pay close mind to the byline, but they are a minority.

Meanwhile, fact-led opinion seems less of an issue with readers, citing polarising news topics like Brexit and lockdown measures. What seems to be the call to action for media organisations: engage in responsible opinion writing? Give greater prominence to less-polarising writers? Resist sensationalist op-eds? Or something else entirely?

“Most people just do not think a whole lot about it or care for it all that much,” explains Toff.

“The ones they did recognise and hold opinions about tended to be presenters or commentators, especially on television.”

Television, as an offline platform, often dominated conversations about trust and it has a big impact on online news perceptions, as audiences do not necessarily see the difference. Equally, news organisations cannot afford to be too segmented here, either.

In India, for example, people had a lot to say about journalists on TV, their personalities, what they liked and disliked about them. But the line between news and entertainment was very blurry. So people were sometimes evaluating these figures in much the same way they would evaluate other kinds of celebrities. Media scholars and journalists traditionally tend not to focus on these dynamics, Toff said.

“A lot of people think the more responsible approach is to remain sceptical toward everything they are seeing in the news – all sources – since it isn’t obvious what differentiates the reporting at one news source versus another.

Toff confirmed that future research will try to quantify how much attention is genuinely afforded to these outspoken personalities and opinion writers, accepting though that it will be hard to collect.

The visibility-invisibility conundrum

Whilst news organisations are, for the most part, aware that clickbait harms trust, this practice is incentivised on digital platforms. This is a problem because the online environment is a minefield of dangerous information, and news organisations seek to be a safe haven of trustworthy content.

Some might say the only thing worse than being a distrusted brand is being a completely invisible brand.”

Benjamin Toff, RISJ

Unfortunately, brands run the risk of being seen as interchangeable with everything else online, including unverified rumours spread by individual accounts and hate speech. But for most publishers, standing out and engaging with young social media users has become a paramount concern.

“Some might say the only thing worse than being a distrusted brand is being a completely invisible brand,” says Toff.

“Some of the things that may maximise clicks and engagement online may not be the forms of journalism with which brands want to be primarily associated with. If news users only ever see your clickbaity headlines, they may know nothing of your enterprise accountability reporting.”

Assurance around hidden agendas

This makes it more pressing to consider longstanding concerns about hidden agendas and secret interests, both commercial and partisan, and that will be a core question for future RISJ research.

Journalists widely consider transparency around news practice a good way to alleviate mistrust. But the report shows that most people do not have a solid understanding of this practice beyond basic familiarity with a handful of brand names. As a result, they tend to apply perceived commercial and partisan agendas to the entirety of the news media as opposed to individual brands.

The competition for attention is so intense.”

Benjamin Toff, risj

Toff said there is an opportunity here for news organisations to better communicate to news audiences what makes them distinct from other news outlets and digital media platforms.

“People need to see clearer, more readily apparent ways how a news organisation’s content differs from the hundreds of other stories that may exist online on similar topics.

“The competition for attention is so intense. It’s about branding really, building associations in the minds of the public, and that’s not going to be something solvable with simple fixes. If news organisations don’t take up the charge of really trying to define the way they are seen by the public, there are plenty of other actors who have a vested interest in discrediting their reporting who will gladly take up the mantle for them.”

This article was originally published on Journalism.co.uk. Did you enjoy what you just read? Sign up for our free daily newsletter.